DR. ELLEN DENHAM | Schubert & Goethe: A Transcendence of Competing Aesthetics

Would Goethe have appreciated Schubert's settings of his poems? It is not difficult to ascertain what Goethe thought about music — he corresponded with the composer Carl Zelter for more than thirty years, came up with an outline for a theoretical system, wrote texts specifically intended to be set to music (including a sequel to Mozart's Die Zauberflöte), and commented frequently about music in his writings. It is not clear how to interpret his near-silence about the work of Schubert. This paper examines recent scholarship on the relationship (or lack thereof) between poet and composer, including Lorraine Byrne Bodley's Schubert's Goethe Settings, Sterling Lambert's Re-Reading Poetry: Schubert's Multiple Settings of Goethe, and Kenneth Whitton's Goethe and Schubert: The Unseen Bond, presenting both sides of the argument regarding whether Goethe would have appreciated Schubert, some additional speculations, and further analysis. The debate has largely been framed by the question of whether Goethe was musical, which might be the wrong question to ask. Perhaps the greatness of Schubert's Goethe settings is partly due to, not in spite of, the two men's different sensibilities. The story of Goethe and Schubert contains a valuable lesson for artistic collaboration: a shared sense of aesthetics is not a prerequisite for creating excellent collaborative art.

Franz Schubert set the words of many poets to music, some great, some lesser, but none a more towering literary figure than Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. Schubert's Goethe settings are argued by many to be among the composer's finest work, approaching a perfect synthesis of music and text. Some scholars go so far as to say there was a special bond or shared outlook between the two men, though we have no proof that they ever met or corresponded. Opinions are divided on Goethe's musicality and whether the poet had a sophisticated understanding of music, based on his reactions or lack thereof to musical settings of his poems. It is not difficult to ascertain what Goethe thought about music: he corresponded with the composer Carl Zelter for more than thirty years, came up with an outline for a theoretical system, wrote texts specifically intended to be set to music (including a sequel to Mozart's Die Zauberflöte), and commented frequently about music in his writings. Given this proclivity, it is not clear how to interpret his near-silence about the work of Schubert. Presenting both sides of the "Was Goethe musical?" debate through additional speculations and analysis will shed some light on the contentious issue of whether Goethe would have appreciated Schubert's settings of his poems. Ultimately, the question may not be so much one of his musicality or lack thereof, as it is of different generations and conflicting aesthetics.

Frederick Sternfeld, writing in Goethe and Music, suggests that arguments that Goethe was unmusical do not present an accurate historical view.1 Sternfeld writes, "The work of Beethoven and Schubert was the subject of great controversy in their time, and it was not until Goethe was past sixty that he had an opportunity to hear compositions by these considerably younger men."

2

While it is fair to point out that the poet and the composer were from different generations — a point to which we will return later — it seems an overstatement to contend that the music of Schubert or Beethoven was highly controversial. Both composers received considerable recognition during their lifetimes, though Schubert much less than Beethoven. Lorraine Byrne Bodley,

3

addressing this subject twenty-four years later, titles the first chapter of her book, Schubert's Goethe Settings, with the very question: "Goethe the Musician?" Byrne Bodley opens the chapter with some colorful quotes by musicologists questioning the poet's musicality, including this criticism by Donald Tovey: "In the vast scheme of Goethe's general culture, music had as high a place as a man with no ear for anything but verse could be expected to give it."

4

Byrne Bodley spends the chapter refuting these claims.

In her introduction, Byrne Bodley states, "I aim to redress the lack of an understanding of Goethe's work in relation to the Schubert settings and to unveil the deep affinity between these artists."5 In her opening chapter, Byrne Bodley details the many ways that music played an important part in Goethe’s life. His parents were both amateur musicians, and the poet had lessons on the piano (for an unspecified period of time beginning at age 14) and later on the cello (1770-71).

6

During the year he studied cello, he progressed enough to read through duets with his teacher.

7

In his memoir he admits that he was not a technically proficient performer on the piano.

8

Thus his musical interests were primarily scholarly rather than based on his own performing experience. Claus Canisius, in the essay "Stranger in a Foreign Land: Goethe as a Scholar in Music" presents an overview of Goethe’s research on music theory culminating in his Tonlehre, an incomplete system in which he explained music in three parts: the organic, the mechanical, and the mathematical.

9

Goethe approached music from these two perspectives: that of folk texts and their accompanying melodies, and that of a would-be theorist. As Canisius’s title implies, music may have been a "foreign land" for the poet, but it was nevertheless a subject that interested him very much. However, as Canisius notes, his scholarship in music was not directed at other scholars, but intended as a manual to “lead directly into the work created by the artists.”

10

This highlights some areas of potential tension—to what extent can a non-musician tell musicians how to create their work? Do the rules of creating poetry necessarily apply in the same way when creating music?

Later in life, Goethe collected folk songs in a variety of languages, and many of his texts are parodies of folk ballads or other works. These are presented in Sternfeld's book, which details the connections between Goethe's texts and earlier poems, noting, for instance, that "Kennst du das Land" from Wilhelm Meisters Lehrjahre is a rhythmical parody of James Thomson's "Summer."

11

Both Byrne Bodley and Sternfeld use Goethe's sense of writing song texts with existing rhythms and melodies in his head as evidence of the poet's musicality. Byrne Bodley also focuses on Goethe's relationship with Carl Zelter, a composer with whom the poet had a long correspondence, though she admits that his relationship with Zelter and with Johann Friedrich Herder "reveals a certain reliance on an interpreter to bring music alive to him."

12

This view is supported by Canisius’s analysis of Goethe’s letter to Herder, in which he asserts that the twelve folk songs Goethe collected from the upper Rhine were a team effort between Goethe and his sister, Cordelia, who was responsible for notating the melodies. Zelter served as an important musical interpreter for Goethe, as documented in their letters spanning 1796-1832, with the last letter by Goethe to Zelter written less than two weeks before the poet's death.

14

Byrne Bodley continues her work on Goethe and Zelter in Goethe and Zelter: Musical Dialogues, in which she presents a substantial body of their correspondence in new translations with commentary and annotations. Again, she vigorously defends Goethe against suggestions he was not appreciative of Schubert’s settings of his poetry, dispelling a common myth about the non-response of Goethe to the packet of songs sent to him in 1816 by Schubert's friend Joseph von Spaun:

Goethe's rejection of Schubert's first book of songs was claimed to have been influenced by Zelter, to whom Goethe supposedly sent the songs for advice. Such arguments are clearly unfounded: in the 891 letters exchanged between these artists there is no mention of Schubert Lieder; on the contrary, the letters prove the dispatch was never sent to Zelter, nor was he in Weimar during the period in which Schubert's first songbook arrived. 15

However, Byrne Bodley can provide no explanation for Goethe's continued silence about Schubert’s music: Goethe acknowledged receipt of a second package of songs from Schubert in his diary in 1825.16 Citing Viennese censorship laws that would require written permission for a dedication to the poet on the title page of Schubert’s published Op. 19 volume, Byrne Bodley theorizes that "a written missive must have been sent to Vienna to allow these songs to be published with a dedication to the poet," but that the letter must have been lost.17 While this may be the case, it does not shed any light on what Goethe may have thought about Schubert’s music.

Byrne Bodley's work is not without its critics. Marjorie Hirsch writes that while Byrne Bodley largely succeeds in some of her arguments in Schubert's Goethe Settings, her tendency to "defend the two artists at all costs" weakens her case.18 Hirsch contends that Byrne Bodley makes excuses for the poet, such as in her argument that "Erlkönig" was rejected by Breitkopf and Härtel the same year Schubert’s friend Spaun sent it to Goethe,19 which may indicate that the publisher also had conservative taste, but does not seem otherwise relevant. Sterling Lambert echoes Hirsch’s criticisms, writing that a better title for the book might be "Goethe’s Poetry that Schubert (Happened to) Set to Music."20 Though he praises the author’s discussion of the poetry, he criticizes her "simplistic" approach to analyzing the music, saying that her "approach…leaves no room for examination of how Schubert’s songs do not simply 'portray' texts but actively interpret them."21 Though Byrne Bodley’s book has many strengths, it ultimately fails to make a convincing case that Goethe and Schubert were kindred spirits and the poet’s lack of engagement with the composer was simply an oversight.

Kenneth Whitton, writing in Goethe and Schubert: The Unseen Bond, takes the argument a step further. Though his book was published in 1999, four years before Schubert’s Goethe Settings, Byrne Bodley does not include it in her bibliography, thus it is unclear if she was familiar with his work. In addition to including a chapter on "Goethe, Music, and Musicians," which makes similar points to those of Byrne Bodley, Whitton devotes an entire chapter to the subject, "Why did Schubert Never Meet Goethe?" He contends that the two men had "much more in common than is generally accepted."22 Responding to critics who say that Goethe would have rejected Schubert’s songs as being non-strophic, he points out that the poet praised a non-strophic setting of "Rastlose Liebe" by Johann Friedrich Reichardt and an "only partly strophic" setting of "Um Mitternacht" by Zelter.23 Whitton goes on to cite Goethe’s Singspiele libretti and poems that focus on or are described by musical imagery, such as the songs of Wilhelm Meister, saying, "Surely, no one who could take the trouble and who possessed the ability to write these could have done so without at least imagining in his head the music that would 'support the words,' as he put it."24 A capacity to imagine music and to write texts that are inherently designed for musical forms, though, does not necessarily imply a high level of musical taste or compositional ability. It is further possible that if Goethe were musical enough to imagine his poetry and poetic songs in a musical context, it might make him reluctant to embrace settings that differ significantly from how he might "hear" the song in his own head. At the end of the chapter, Whitton engages in a tantalizing speculation: "what if the two artists had met?"25 Schubert, he imagines, may have earned the recognition he deserved with the support of the poet, and Goethe might have found a true collaborator who "had the genius to marry the texts to great music."26 This would seem to be more likely if the two men were from the same generation, as Goethe (1749-1832) and Zelter (1758-1832) were, rather than being separated by forty-eight years in the case of Schubert. Perhaps the gap between them was one of both generation — as suggested earlier by Sternfeld — and aesthetics, which will be investigated below. Considering the poet’s written views about music and thoughts on other settings of his texts, however, it is difficult to imagine him embracing the music of the younger Schubert.

Criticism of Goethe’s musical taste comes from multiple sources. Byrne Bodley includes among these Ernst Walker, Moritz Bauer, Elizabeth Schumann, Calvin Brown, and the aforementioned Donald Tovey, who called Goethe "a man with no ear for anything but verse."27 Hans Keller further asserts in his essay "Goethe and the Lied," that on the topic of music, "the only thing one can say about Goethe in this context is that he was genuinely, profoundly unmusical; and it is this fact which, to my knowledge, hasn’t yet been demonstrated."28 Keller uses the composer’s own writings to level this charge, analyzing the poet’s arguments in a 1799 essay on dilettantism and concluding that "the only thing Goethe has to add about the art of music is that it is a subjective art springing from the pleasure-drive (the Lusttrieb)."29 He goes on to, among other arguments, state that the best settings of Goethe’s poems are based on "meaningful contradictions," a tension that occurs when the implied meter of the text and may seem to contradict the rhythm of the music.30 Keller’s overview includes Schubert’s settings of "Meersstille," which he praises for its "deliberate friction…between the music’s harmonic rhythm and the metre of both the music and the poem,"31 and "Wanderers Nachtlied," which he says "expresses a wealth of contrasting, yet continually consistent, emotions such as no other composer – with the possible exception of two – has ever conveyed within a comparable space."32 Keller makes an important point: effective musical settings of poetry do not always need to follow the text precisely in terms of meter, text repetition, and imagery. After all, music often represents the subtext, or inner thoughts, of the song’s protagonist, which may be quite different from the sung words. Nowhere is this more clear than in Schubert’s setting of Goethe’s "Gretchen am Spinnrade," in which the spinning wheel slows, stops, and only gradually restarts as Gretchen’s spinning is disrupted by her thoughts of Faust’s kiss.

Keller’s arguments fit with much of what is known about Goethe’s musical experience and taste. In the preface to his edition of Goethe songs by lesser-known composers such as Zelter, Richard Green presents some historical context for the role of the Lied and Goethe’s experience with it. Green’s thoughts parallel those of Keller when he says "Schubert’s contribution to the history of the genre was not only to create Lieder of inestimable value and sensitivity, greater than those of the previous generation, but in doing so he asserted his own reading of the poetry over that of the poet’s."33 In a section titled "The Lied in the Age of Goethe," Green summarizes the role of Lieder in Goethe’s time: rarely performed in public but in small salon or home settings (Hausmusik), composed in a folk style, and deemed appropriate for relatively simple musical settings suitable for amateur singers.34 He goes on to say, "As this definition, and others like it written toward the middle of the century, does not acknowledge the richness that Schubert had imparted to the genre, it appears that the discussion is based on works of the previous generation, or that it intentionally ignores songs in more complex forms."35 Schubert’s work, then, is part of a stylistic turning point away from the aesthetic of Zelter and Reichardt, both praised by Goethe, away from what Green terms "the Biedermeier ideals of simplicity and innocence"36 and toward a new, Romantic style.

Was Goethe really so unmusical as Keller and Tovey might claim, or was he simply a member of an older generation and an opposing aesthetic camp? Whether his lack of response to Schubert indicates a distaste for the composer’s settings of his poems is debatable. Byrne Bodley cites an April 1830 account by German bass-baritone Eduard Genast detailing Goethe’s response to a performance of Schubert’s "Erlkönig" by Wilhelmine Schröder-Devrient, in which Goethe is reported to have said, "I heard this composition once before when it did not appeal to me. But performed like this, the whole song shapes itself into a visible image."37 Though this may seem less an endorsement of Schubert than of the skills of the performers, it does indicate a positive response to the song upon a second hearing. Little else is known about Goethe’s response to Schubert; however, his comments on Beethoven and composers with similar aesthetics have been recorded. Sternfeld writes, "It was incomprehensible to him that Beethoven and Spohr should mistake Mignon’s song Kennst du das Land wo die Zitronen blühn so completely by making it durchkomponiert [through-composed]."38 He goes on to quote Goethe as having said, regarding both composers:

I should have thought the same marks which recur in each of the three stanzas at the same place would have been sufficient to indicate to the composer 39 that I expected from him nothing but a Lied. Mignon, according to her character, can sing a Lied but not an aria. 40

Goethe's point is well-taken in consideration of how specific he was in the text of Wilhelm Meister regarding Mignon's songs. "Kennst du das Land" appears at the opening of Book III, as the child Mignon sings it for Wilhelm. Pleased with the song, Wilhelm asks her to repeat it, writes the stanzas down, and translates them as best he can, "but the originality of its turns he could imitate only from afar; its childlike innocence of expression vanished from it in the process of reducing its broken phraseology to uniformity, and combining its disjointed parts. The charm of the tune, moreover, was entirely incomparable."41 Goethe continues to describe the manner of Mignon's singing, sometimes "stately and solemn," becoming "deeper and gloomier" in the third line, and dahin (to there) repeated with a "boundless longing."42 This evocation creates at the same time a helpful aid and an impossible conundrum for a composer. The poet's words paint a detailed picture of both Mignon and her song, even a performance practice, but at the same time the context surrounding the song in the novel presents a paradox. Which version is a composer to evoke, the childlike, simple one of Mignon, or Wilhelm's recorded attempt at a translation? It is fundamentally not possible to set the childlike verse because what is presented to the reader is already a transcription via Wilhelm, described as lacking the original’s innocence at the cost of uniting its disparate elements.

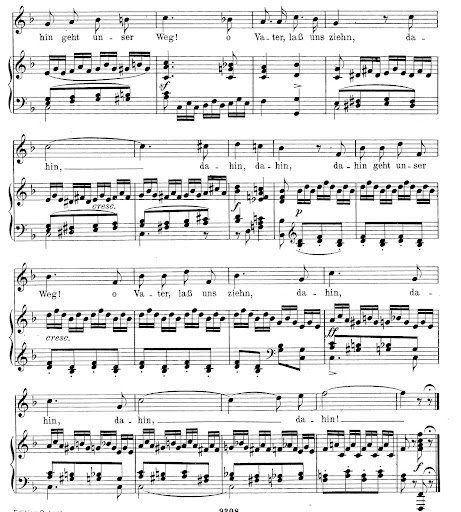

Fig. 1-excerpt from "Kennst du das Land" D. 321

If Goethe objected to the aria-like nature of Beethoven's setting and the repetition of the word "dahin" beyond the two times it appears in each stanza of the poem, as well as the repetition of larger textual phrases, it is reasonable to imagine he might have a similar reaction to the setting Schubert composed in 1815, which does not preserve the pacing of each strophe as it might be recited, but changes the tempo from moderato to allegro, e molto appassionato for the closing of each verse and contains a total count of eleven "dahins," not two, per stanza.

[fig.1]43

It may be difficult to understand what made Goethe so irritated about Beethoven and Spohr’s text repetition when the settings still conveyed the spirit of his poem without delving more deeply into the subject of musical parody. Sternfeld is careful to distinguish the creative practice of parody in music (dating at least back to parody masses in the Renaissance) from the negative connotations of the word, writing that "Goethe and his contemporaries, as well as his forebears, wrote parodies by creating new texts to older tunes and rhythms, without any implication of irony."44 To understand the concept of parody by means of a rougher but more easily illustratable example than Goethe's works, we will examine a poetic form with which every English speaker is familiar: the limerick. It is nearly impossible to read the Edward Lear poem below without reading it in the correct rhythm (try it):

There was a Young Lady whose chin,

Resembled the point of a pin;

So she had it made sharp,

And purchased a harp,

And played several tunes with her chin. 45 Now, imagine Goethe writing a poem with a very specific rhythm implied, perhaps obtained from a particular folk song that may be as obvious to him as the limerick to us. If he were to hear a setting that completely disregarded this rhythm, it could certainly impinge upon his ability to fairly listen to the musical setting, as appears to be the case with his comments about Beethoven and Spohr. And as demonstrated above, in Wilhelm Meister Goethe engaged with song in a very prescribed way that did not leave much room for interpretation to the composer.

Because Goethe's musicality has been called into question, it is only fair to bring up the parallel subject of Schubert's literary tastes. Schubert composed over 600 songs; only a fraction of these set texts by important poets like Goethe. Donald Tovey attests that Schubert's friend Mayrhofer "was no Goethe" and gives middling praise to Wilhelm Müller, though he notes that Schubert's musical genius transcended any weaknesses in these texts.

46

Maurice Brown, discussing Schubert's failed opera Der Graf von Gleichen, D 918, comments on the composer's "extraordinary inability" to tell a good libretto from a bad one.

47

Marius Flothius, however, writing in the essay "Franz Schubert's Compositions to Poems from Goethe's Wilhelm Meisters Lehrjahre," defends Schubert's use of the poetry of his friends by saying that the poems Schubert set, though not all are well-regarded today, "met the needs of the public" at the time.

48

Part of the excitement of scholars about Schubert's Goethe settings stems from the fact that not one, but both men were each giants in their art — how wonderful to see their words and music collaborate on the page and in the concert hall!

Though despite his efforts, Schubert did not have a personal relationship with Goethe, he certainly had a very close engagement with the poet's texts. Schubert not only set Goethe's poems, but revised and recomposed them, sometimes in multiple versions. In particular, he set another one of Wilhelm Meister’s songs, "Nur wer die Sehnsucht kennt," six times, including once as a duet for Mignon and the Harper, just as Goethe describes it in the novel. Byrne Bodley notes that this "is the only duet among the important interpretations,"

49

demonstrating that Schubert understood the context of the poems. Schubert's engagement and reengagement with Goethe's texts is the subject of Sterling Lambert's book, Re-Reading Poetry: Schubert's Multiple Settings of Goethe. Lambert, who was earlier cited in his critique of Lorraine Byrne Bodley, does include her work in his bibliography as well as that of the aforementioned Kenneth Whitton. Lambert also makes a statement that echoes theirs when he comments on an "important shared outlook between composer and poet."

50

One might argue that because of their aesthetic differences, they could not have shared an aesthetic vision; however, perhaps it is the difference in their perspectives that makes Schubert's Goethe settings greater than the sum of the text or the music — a bridge between the past and the future. Lambert focuses particularly on the fascination that the character Mignon must have held for Schubert, as he made more than twelve settings of her songs, including some fragments. He even suggests that Schubert may have returned to the Mignon songs for the last time in 1826 because of a possible identification with the character's secret — her incestuous birth — due to Schubert's own secret — his suffering from syphilis

51

— though Lambert is quick to note that this is pure speculation. To be sure, the Mignon Lieder remained significant throughout Schubert's compositional life, and the four Mignon songs, D 877 Op. 62, were his last settings of Goethe’s texts.

Because the scope of this article does not permit space for a lengthy analysis of Schubert’s songs in terms of their relationship to Goethe’s original texts, his final solo setting of Lied der Mignon, D 877 Op. 62 No. 4, will be examined in brief as an example. In Goethe's Wilhelm Meister, the song appears as an "irregular duet" between Mignon and the Harper, who is later revealed to be Mignon's father.

52

Schubert set two versions in his Opus 62, one as a solo, the other as a duet. The poem comes at the end of Book III, Chapter XI. Wilhelm falls into a "dreamy longing," and the duet that Mignon and the Harper sings is "accordant with his feelings."

53

Goethe's text is as follows:

Nur wer die Sehnsucht kennt,

Weiß, was ich leide!

Allein und abgetrennt

Von aller Freude,

Seh' ich ans Firmament

Nach jener Seite.

Ach! der mich liebt und kennt,

Ist in der Weite.

Es schwindelt mir, es brennt

Mein Eingeweide.

Nur wer die Sehnsucht kennt,

Weiß, was ich leide!

After a six-bar A-minor prelude in 6/8, Schubert's D 877 solo setting states, then repeats, the initial couplet, making the first strophe irregular through phrase repetition. A D-sharp in the right hand of the accompaniment intrudes plaintively against an E in the bass at measure 8 to underscore the first utterance of the word "Sehnsucht." But an even more significant departure from Goethe's text comes in the second strophe. The accompaniment completely changes character, with a frenzied series of diminished seventh chords in sixteenth note sextuplets and triplets, punctuated with sixteenth rests like little gasps. This underscores the text "Es schwindelt mir, es brennt / Mein Eingeweide" ("it makes me faint, it burns / my innards") which is sung in a rapid burst of declamation, and imbues it with a sense of genuine drama, as if the character's emotions are almost out of her control. This would not be possible in a purely strophic setting, and it is what gives the song its true genius. The listener can imagine Mignon’s feelings rapidly shifting from that of longing to a moment of unbearable anguish — breaking out of the constraints of poetic meter — before exhausting herself in her outburst and returning, simply, to sadness. Like Gretchen's spinning wheel, the accompaniment gradually slows down and stops beneath a fermata, before Schubert repeats the opening vocal line and its accompaniment figure with the opening text (mirroring the original text repetition at the end of Goethe's second strophe). This time, however, the line "Nur wer die Sehnsucht kennt" ascends to a sforzando forte, as if Mignon is building to another outburst, before running out of energy and finishing the song as simply as it began.

[fig. 2]54

Fig. 2 – Excerpt from "Lied der Mignon" from 4 Gesänge aus 'Wilhelm Meister', D.877

Is this reading true to Goethe's text? Lambert says about the other two texts in Op. 62, "both songs seem less the outpourings of a twelve-year old girl than of the fully grown woman that she never actually lives to become."55 The same could be said of Schubert's final setting of "Nur wer die Sehnsucht kennt." Both Lambert and Whitton note that this work is based on another Schubert Lied, a setting of the Johann Gaudenz von Salis-Seewis poem "Ins stille Land," from ten years earlier.56 Part of the melody and accompaniment, then, predate their later association with the character Mignon and her song. The new material comprises the "outburst" in the second strophe. While the reading may not be true to Goethe's text in a literal, metrical sense or true to the character as she appears in the novel, it represents a powerful depiction of the suffering of Sehnsucht that seems in the spirit of Goethe's poem, or at the very least, does no harm to the poet's text. Though not as well-known as "Erlkönig" or "Gretchen am Spinnrade," it encapsulates the anguish of an insatiable longing into a brief, yet powerful package. Would the poet have approved? A look at the comparatively sedate, but literal setting of this text by Zelter and consideration of Goethe's feelings about Lieder suggest otherwise. (Zelter's purely strophic setting is certainly not unpleasant but arguably lacks the emotional impact of Schubert's.)

Why is a literal reading of the text not always the most powerful way to set a poem? There is a difference between being faithful and being overly literal, between creatively engaging with a work and aping it. When transforming something from one art (poetry) to another (music), a literal translation may not even be possible. If it were so, the words Goethe used to describe the context of "Kennst du das Land," from Mignon’s performance to Wilhelm’s translation, would be an easy roadmap for a composer to follow. Goethe, in his novel, translated music into poetry by giving Wilhelm words to describe and translate Mignon's song. He did so beautifully because he did not attempt to give a literal account of the exact words the child sings, but described her manner of singing and translated the text himself (via Wilhelm) into a poem. Hans Keller calls composing to a text literally as "creatively passive."57 Keller recounts a story by Schoenberg in which the composer was ashamed that he knew Schubert's songs well but knew nothing about the texts. Upon reading the poems by Goethe and others, Schoenberg found he hadn't missed anything; Schubert had made the meaning of the poem so clear through his music that reading the poem was almost redundant.58 Rather than disparaging Goethe's poems, this is a testament to the genius of both artists.

It is one thing to understand, appreciate, and have technical or theoretical knowledge about music. It requires an additional skill set to compose it or to instruct others in how to do so. Goethe knew enough about music to have strong opinions and a definite aesthetic sense—that did not mean he had the skill to recognize greatness in something that may either differ from his own innate aesthetic sense or be outside the bounds of what he could imagine, while thinking literally about music as something that simply translated a text.

It is instructive to speculate on the relationship or lack thereof between Goethe and Schubert, especially since Goethe remains an important literary figure and Schubert's settings of his poems remain among the finest examples of Lieder. Though one cannot change history, scholars still enjoy games of "What if?" such as Kenneth Whitton's musings about the implications of a collaboration between Goethe and Schubert, or Sterling Lambert's hypothesis about Schubert's personal identification with Mignon. It is equally tempting to defend Schubert from Goethe's implied rejection by calling the poet "unmusical," as does Hans Keller, or to vociferously defend Goethe against such attacks, as does Lorraine Byrne Bodley. There seems to be a tension that is not possible to reconcile, in the absence of a historical record explicitly stating each artist’s opinion about the other. However, examining the various arguments causes one to speculate as well. Perhaps Goethe was not unmusical, but of a different artistic generation and circle from Schubert, well-enough versed in music and conservative enough in his tastes to be firm in his more Classical aesthetic, while Schubert was on the forefront of developing something new. One can hardly fault the latter for being a man of his time. Sebastian Urmoneit considers some of these ideas, saying "It is not enough to see [Goethe's preference for Zelter over Schubert] as a manifestation of Goethe's lack of musical expertise; rather, a comparison of settings by the two composers reveals the realm of aesthetic tension between Classicism and Romanticism in which Goethe located his own poems."59 This seems a reasonable middle ground. Lambert hints at this issue in a different context when he writes that Schubert's desire to reset Goethe texts and the differences between the earlier and later settings may be "symptomatic perhaps of a more subjective and personal approach to poetry that might be said to lie at the heart of the emerging transition from musical Classicism to Romanticism."60 Sternfeld seems to agree; though he writes about Goethe and Beethoven rather than Schubert, the sentiment is clearly applicable to both:

We must not quarrel with either the poet or the composer. Each had a higher destiny to follow than mere mutual compatibility…[examining Goethe's parodies and ideal of song] will, perhaps, lead us to drop the old and sterile question, "Was Goethe Musical?" with the realization that the term "musical" has different meanings in different cultural contexts. Who are we to impose later concepts on a poet whose work sprang from music and demanded music as its complement? 61

Perhaps the story of Goethe and Schubert contains some broader lessons. First, genius in one art does not imply genius in another. Though Schubert was certainly literary, he did not set equally high quality texts to music over the course of his career. Though claims that Goethe was completely unmusical are hyperbolic, the poet's conception of song was rather limited. Composers who aim to write their own lyrics and poets who seek to compose songs to their texts should take heed, as well as any artists who wish to collaborate with others who may have different aesthetic sensibilities. Second, a successful artistic collaboration does not necessarily depend upon artists being in aesthetic agreement, or even working together at all. Maybe Schubert and Goethe could have collaborated to their mutual benefit, but it seems equally likely that the older poet may have denied Schubert the freedom to engage with the texts using his own dramatic sensibility. It is a frightening thought to contemplate how this relationship might have played out under the aegis of modern copyright law. Would Goethe have prevented publication of songs by Schubert or Beethoven? We are extremely fortunate to have both the work of Goethe, in print and in the various musical incarnations set by multiple composers, and the work of Schubert, including his musical interpretations of Goethe, to study and listen to and sing and play and argue about for times to come.

Notes

- Frederick W. Sternfeld, Goethe and Music: A List of Parodies and Goethe's Relationship to Music; A List of References (New York: Da Capo Press, 1979), 7. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- The author is published here under the name "Lorraine Byrne." ↩

- Donald Francis Tovey, "Franz Schubert," Essays and Lectures on Music (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1949), 103. ↩

- Lorraine Byrne, Schubert's Goethe Settings (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2003), xvii. ↩

- Byrne, 3-4. ↩

- Claus Canisius, "Stranger in a Foreign Land: Goethe as a Scholar in Music," Goethe and Schubert: Across the Divide, Proceedings of the Conference 'Goethe and Schubert in Perspective and Performance,' Trinity College Dublin, ed. Lorraine Byrne and Dan Farrelly (Dublin: Carysfort Press, 2003), 20. ↩

- Byrne, 3. ↩

- Canisius, 33. ↩

- Ibid, 31. ↩

- Sternfeld, 34. ↩

- Byrne, 6. ↩

- Canisius, 22. ↩

- Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Carl Friedrich Zelter, and Arthur Duke Coleridge (trans.), Goethe's Letters to Zelter, with Extracts from those of Zelter to Goethe (London: G. Bell and Sons, 1887), 490. ↩

- Lorraine Byrne Bodley, Goethe and Zelter: Musical Dialogues(Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2009), 4. ↩

- Ibid., 5. ↩

- Ibid., 5. ↩

- Marjorie Hirsch, "Book Reviews: Historical and Analytical Studies - 'Schubert's Goethe Settings' by Lorraine Byrne," Quarterly Journal of the Music Library Association 60.4 (June 2004), 963-964. ↩

- Ibid., 964. ↩

- Sterling Lambert, "Review: Lorraine Byrne, Schubert's Goethe Settings,"Eighteenth-Century Music 3/1 (2006), 142. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Kenneth Whitton, Goethe and Schubert: The Unseen Bond (Portland, OR: Amadeus Press, 1999), 131. ↩

- Ibid., 132. ↩

- Ibid., 133. ↩

- Ibid., 147. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Byrne, Schubert's Goethe Settings, 3. ↩

- Hans Keller, "Goethe and the Lied," Goethe Revisited, ed. Elizabeth M. Wilkinson (London: John Calder Ltd., 1984), 74. ↩

- Ibid., 74-75. ↩

- Ibid., 77. ↩

- Ibid., 80. ↩

- Ibid., 82-83. The other two composers Keller believes succeeded at this are Chopin and Gershwin. ↩

- Richard D. Green, preface to Anthology of Goethe Songs [Zelter et al.], Recent Researches in the Music of the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries, Vol. 23 (Madison, WI: A-R Editions, 1994), vii. ↩

- Ibid., vii-viii. ↩

- Ibid., ix. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Byrne, Schubert's Goethe Settings, 22. ↩

- Sternfeld, 21. ↩

- Here Goethe uses the term “Tondichter,” literally "tone-poet," rather than "Komponist," "composer," which may give insight into his thoughts about music (and musicians) being first and foremost servants of the text. ↩

- Ibid. Sternfeld's source for this quote is not clear. ↩

- Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, trans. Thomas Carlyle, Wilhelm Meister's Apprenticeship and Travels, (London: Chapman and Hall, 1890), 120. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Franz Schubert, Kennst du das Land, ed. Max Friedlaender (Leipzig: Edition Peters, n.d.) accessed September 9, 2023, 224. ↩

- Sternfeld, 8. ↩

- Edward Lear, A Book of Nonsense, Edward Lear Home Page. http://www.nonsenselit.org/Lear/BoN/bon020.html ↩

- Tovey, 128-129. ↩

- Maurice J.E. Brown,The New Grove Schubert, ed. Stanley Sadie (London: MacMillan, 1980), 51. ↩

- Marius Flothius, "Franz Schubert's Compositions to Poems from Goethe's Wilhelm Meisters Lehrjahre," Notes on Notes: Selected Essays by Marius Flothius. Trans. Sylvia Broere-Moore. (Amsterdam: F. Knuf, 1974), 89. ↩

- Byrne,Schubert's Goethe Settings, 268. ↩

- Sterling Lambert, Re-Reading Poetry: Schubert's Multiple Settings of Goethe (Woodbridge, Suffolk: The Boydell Press, 2009), preface. ↩

- Ibid., 255. ↩

- Goethe, 196. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Franz Schubert, Lied der Mignon, ed. Max Friedlaender (Leipzig: Edition Peters, n.d.), accessed September 9, 2023, https://imslp.org/wiki/File:PMLP39443-Schubert_Album_Band_1_hoch_Peters_71_Lied_der_Mignon_scan.pdf ↩

- Lambert, 222. ↩

- Ibid., 225. ↩

- Keller, 83. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Sebastian Urmoneit, "Mignons Sehnsucht: Versuch über Goethe, Zelter und Schubert," Schubert: Perspektiven, 2(1), English abstract. ↩

- Lambert, 255. ↩

- Sternfeld, 22. ↩

References

- Brown, Maurice. The New Grove Schubert. London: MacMillan, 1980.

- Bodley, Lorraine Byrne. Goethe and Zelter: Musical Dialogues. Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2009.

- Byrne, Lorraine. Schubert's Goethe Settings. Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2003.

- Canisius, Claus. "Stranger in a Foreign Land: Goethe as a Scholar in Music." In Goethe and Schubert: Across the Divide, Proceedings of the Conference "Goethe and Schubert in Perspective and Performance," edited by Lorraine Byrne and Dan Farrelly, pp. 19-36. Dublin: Carysfort Press, 2003.

- Flothius, Marius. "Schubert's Compositions to Poems from Goethe's 'Wilhelm Meister's Lehrjahre.'" Notes on Notes: Selected Essays by Marius Flothius. Trans. Sylvia Broere-Moorel. Amsterdam: F. Knuf, 1974.

- Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von and Carl Friedrich Zelter. Goethe's Letters to Zelter, with Extracts from those of Zelter to Goethe. Trans. Arthur Duke Coleridge. London: G. Bell and Sons, 1887.

- Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von. Wilhelm Meister's Apprenticeship and Travels. Trans. Thomas Carlysle. London: Chapman and Hall, 1890.

- Green, Richard D. Anthology of Goethe Songs. Recent Researches in the Music of the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries v. 23. Madison: A-R Editions, 1994.

- Hirsch, Marjorie. Book Reviews: Historical and Analytical Studies – 'Schubert's Goethe Lieder' by Lorraine Byrne.'" Quarterly Journal of the Music Library Association 60.4 (June 2004): 963-964.

- Keller, Hans. "Goethe and the Lied." Goethe Revisited, edited by Elizabeth M. Wilkinson. London: John Calder Ltd., 1984.

- Lambert, Sterling. Re-Reading Poetry: Schubert's Multiple Settings of Goethe. Rochester, NY: Boydell Press, 2009.

- Lambert, Sterling. "Review: Lorraine Byrne, Schubert's Goethe Settings." Eighteenth-Century Music 3/1 (2006): 142.

- Lear, Edward. A Book of Nonsense. Reproduced on Edward Lear Home Page. http://www.nonsenselit.org/Lear/BoN/bon020.html

- Schubert, Franz. Kennst du das Land. Edited by Max Friedlaender. Leipzig: Edition Peters, n.d. Accessed September 9, 2023. https://imslp.org/wiki/File:PMLP36241-schubert_kennst_du_das_land_high_voice_peters_9308.pdf

- Schubert, Franz. Lied der Mignon. Edited by Max Friedlaender. Leipzig: Edition Peters, n.d. Accessed September 9, 2023. https://imslp.org/wiki/File:PMLP39443-Schubert_Album_Band_1_hoch_Peters_71_Lied_der_Mignon_scan.pdf

- Sternfeld, Frederick W. Goethe and Music: A List of Parodies and Goethe's Relationship to Music: A List of References. New York: Da Capo Press, 1979.

- Tovey, Donald Francis. "Franz Schubert," Essays and Lectures on Music. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1949.

- Urmoneit, Sebastian. "Mignons Sehnsucht: Versuch über Goethe, Zelter und Schubert." Schubert: Perspektiven 2.1, 2003.

- Whitton, Kenneth. Goethe and Schubert: The Unseen Bond. Portland, OR: Amadeus Press, 1999.

November 9, 2023